When the sky is a hunting ground

Share

Originally published by Pulsar. Find the Original here

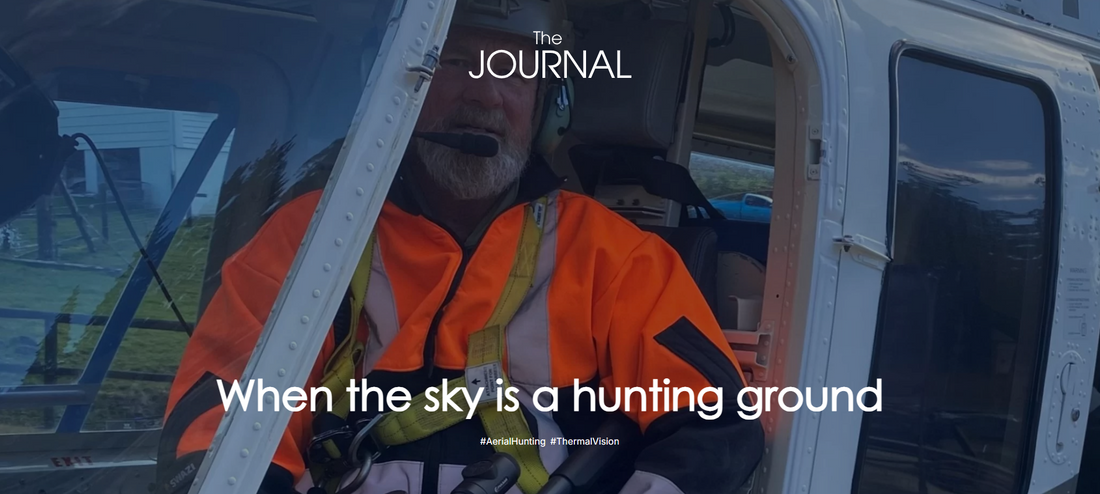

Meet Ian Cox, a New Zealand-based hunter with thirty years of experience in the field. While you may find him on the ground controlling pests in local wetlands and forests, his real expertise is in the air. Ian is a master of aerial hunting, one of the most efficient and legal methods for wildlife management in New Zealand, though it is rare in many other countries due to legal restrictions.

Ian, could you tell me how you got into Thermal Assisted Aerial Control? What was the start for you?

It all started over 10 years ago. My first time out was with a man named Ant Corke. I can’t remember how we first met, but I recall taking him on an aerial pig control trip to Farewell Spit.

Toby Reid, whose family are well-known aviation legends here in New Zealand was our pilot.

At one point, I remember Ant communicating through the intercom, “There’s a smudge over here.” So, we started chasing pigs, and it was a cool experience.

Ant was in the rear of the helicopter spotting pigs with a Pulsar handheld device. We would pursue the pigs through the reeds and low stature bush until a clear shot was able to be taken. We never used the thermal sights back then.

We did numerous TAAC sorties at Farewell Spit and took the method to other areas, such as Abel Tasman National Park and Kahurangi National Park.

You hunt both on the ground and in the air. How does hunting from a helicopter work?

As a hunter, I do government and non-government work. As for the government, the full team – the pilot, the shooter, and the thermal camera operator – must go through an assessment and verification process to prove they are capable of this work and follow a certain standard. It’s pretty much like the aircraft, which must follow a specific maintenance schedule. It is quite a hazardous job, as sometimes we fly not only at altitude, but also down in the canopy of the forest, in quite restricted and confined areas where you don’t have much room, with big winds and the risk of stuff getting stuck in the blades. The way you’re held in the helicopter is also important.

We also like to think of the worst-case scenario – for instance, if you crash and hang upside down, stuck with your belt on, you might end up getting burnt to death. For these situations, we have a so-called three-ring system, which allows quick and safe detachment of the harness in case of emergency.

You mentioned you already started using ballistics – how does that equipment fit into aerial surveys?

Yes, I started using ballistics in June or July last year, when I was on a delimitation survey of the goat population, which took place in Kahurangi National Park. The primary goal was to shoot goats from the air, a task that requires specific equipment and techniques. It was windy at one point, so I zeroed the rifles and used a Knight’s Armament AR15 223 KS – a nice piece of kit, which is effective for shooting goats even up to 300 meters. It’s low-recoil and easy to use with a thermal sight. DPMS Panther 308, on the other hand, made it harder to maintain a stable sight with a heavy recoil.

The helicopter type is also important, as some are nimbler for close-up work and others, such as the Bell 206 Long Ranger that we used, are better for stable, long-range shooting. You also must maintain a safe distance from the terrain, especially ridges, to avoid wind turbulence and to prevent ricocheting debris from damaging the helicopter’s blades. So, you’ve got to sit back and shoot down rather than straight out. I used specific ballistic tables to make quick, precise shots from as far as 250 meters, spotting goats in the scrub even when the pilot couldn’t. If something goes wrong on the ground, it’s one, but when you’re flying in the air… In New Zealand, these helicopters are like 2500-300 dollars an hour, so if you must fly back, it might cost you a couple of grand.

What does success look like in the context of pest control?

There are different levels of success depending on the goal. So basically, there’s eradication, which is the most difficult one, as this is usually sought on islands or in fenced-off areas where it’s possible to eliminate the entire population. Then there is zero density, meaning that while some animals might be present, their population isn’t growing. Lastly, a more manageable level is low numbers, when a small number of pests can be tolerated without significant negative impact. When using ground teams with dogs, success is measured by the number of animals hunted per “man day”, which is defined as 8 hours a day. Both dogs and hunters must meet specific standards. You can’t take any dog; it must be ticked off as a wild animal detection dog.

The hunters must meet a certain standard, a metric called a Seedling Ratio Index, used to measure the health of native flora. Certain palatable plant species are only eaten by pests once they grow to a certain height – about 300 millimeters. So, they measure the number of palatable seedlings below and above this standard and assess the browse damage of the plants. This data shows that if a team can hunt two or fewer animals per man-day, it indicates that plant regeneration is occurring. If the goal is to protect a specific threatened or endangered plant species, the pest control efforts must aim for a zero-density outcome.

How do you prioritize which areas and species to work on?

We basically look at the integrated control. You try to pick a fight that you can win. But it changes a bit depending on the time and place. For example, on offshore islands, they try to go for eradication, as they are far enough away from the mainland to stop stoats, which can swim up to a bit less than 2 kilometers. Therefore, if an island is more than 2 kilometers away from the mainland, it is considered a good candidate for an eradication program because it is less likely to be re-invaded by stoats swimming back. Rats will go further, deer – even further, as for goats, they don’t like water at all, so it’s complex.

How do thermal devices level up your hunting experience?

The great thing about using thermals is that they remove a lot of risk. We don’t have to do any crazy acrobatics to get to the animals. They’ll often run into the forest and stop because they think we can’t see them anymore. They don’t realize that with the thermal scope, we can still spot them perfectly well, so we can just stop shooting when they’re out of sight and then take a clean shot once they’ve settled down.

Sometimes, if they run into thick scrub, the pilot can get the helicopter down low and blow some cold air on them. They don’t like that, and they’ll start moving, making it easier to see and shoot. It’s a game-changer.

If you could design the ultimate thermal scope, what would it be?

Right now, I’m using a Thermion 2 LRF XP50. It’s a few years old but still works great. I have it set with a green circle and a small cross for the reticle – that just works for my eyes. It never let me down, though sometimes I need to do a manual reboot or reset it.

Honestly, the Pulsar scope I’m using is already great. If I could design the ultimate one, I’d only change a couple of things. I’d make it a bit lighter and give it a slightly wider field of view. But other than that, it’s pretty much what I’m using now. I mean, show me something better, right?